The European Parliament's role in EU economic governance: Evolution, implementation, and future prospects

The European Parliament's role in EU economic governance: Evolution, implementation, and future prospects

by Samuel De Lemos Peixoto, and Giacomo Loi, Administrators for a parliamentary body, Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit, European Parliament(*)

Citer cet article: De Lemos Peixoto, Samuel, & Loi, Giacomo. The European Parliament's role in EU economic governance: Evolution, implementation, and future prospects. Revue de l'euro, n°58, 2025. https://doi.org/10.25517/revue-euro-2025-58-5

Introduction

The European Union's economic governance framework has undergone profound transformation since the global financial crisis, evolving from a relatively simple set of fiscal rules into an increasingly complex system of economic policy coordination and surveillance.[1] This evolution has raised fundamental questions about democratic accountability and parliamentary oversight[2] in a domain where executive decision-making has become increasingly technocratic and intertwined between national and European levels.

The challenge of ensuring effective parliamentary oversight in EU economic governance is threefold. First, there is the question of the appropriate level of scrutiny - should parliamentary control be centralised in the European Parliament, exercised primarily by national parliaments, or shared between both levels? Second, there is the challenge of overseeing an increasingly complex web of procedures and instruments, from the European Semester to the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which operate through both EU and intergovernmental mechanisms.[3] Third, there is the practical difficulty of coordinating oversight between parliaments at different levels while respecting their distinct roles and competencies.

These challenges are compounded by an inherent tension between different visions of parliamentary oversight in the EU. In line with Treaty provisions, the European Parliament generally advocates for a model of centralised oversight, positioning itself as the primary parliamentary body for scrutinising EU-level decisions. Many national parliaments, by contrast, push for a model of joint oversight, arguing that the multilevel nature of EU economic governance requires coordinated parliamentary scrutiny at both European and national levels. This tension manifests in debates over the scope and strength of interparliamentary cooperation mechanisms.

The evolution of the EU's economic governance framework reflects these ongoing challenges. The foundation rests on three key Treaty provisions:

- Article 121 TFEU establishes the framework for economic policy coordination

- Article 126 TFEU sets out the excessive deficit procedure

- Article 136 TFEU enables enhanced coordination for euro area countries

This framework was substantially strengthened through the Six-Pack (2011) and Two-Pack (2013) regulations, which introduced stronger surveillance mechanisms and new sanctions procedures. The European Semester was established as an annual cycle for coordinating economic policies across Member States. Most recently, the Recovery and Resilience Facility has added a new dimension focused on supporting reforms and investments aligned with EU priorities.

Throughout these developments, the role of parliamentary oversight has evolved significantly but remains contested. While the European Parliament's powers have expanded from a largely consultative function to becoming an active participant in economic policy oversight, questions persist about the effectiveness of parliamentary scrutiny and the appropriate balance between European and national parliamentary prerogatives.

This paper examines these challenges by analysing: the European Parliament's evolving role in economic governance (Section II); the experience of the first decade of reformed economic governance from 2011-2021 (Section III); the Parliament's role in the new economic governance framework (Section IV); and the development of interparliamentary cooperation (Section V).

Through this analysis, we aim to better understand both the progress made and the persistent challenges in ensuring democratic accountability in EU economic governance.

The European Parliament's Role in Economic Governance

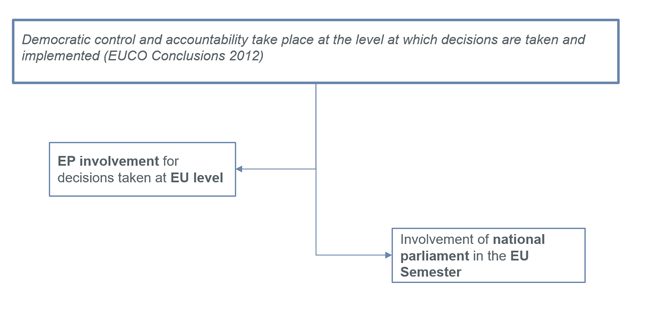

Figure 1: Involvement of European parliaments in multilevel fiscal governance

Source: Authors’ own elaboration

The involvement of parliaments in EU economic governance reflects a fundamental principle: democratic control and accountability should take place at the level where decisions are taken[4]. However, implementing this principle in practice is complex given the multi-layered nature of EU fiscal governance, where responsibilities are shared between EU executive actors and national authorities. This section analyses how the European Parliament's oversight role has been institutionalised through both primary and secondary legislation, and how this role has evolved through more recent initiatives like the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

Primary legislation - Treaty Foundations

The involvement of the European Parliament in the European economic governance is enshrined in primary legislation.[5]

Following the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon, Article 121(6) of the TFEU has explicitly recognised the European Parliament’s role as a co-legislator by allowing to set down detailed rules on multilateral surveillance procedures by means of ordinary legislative procedure. In paragraph 5, the same article also lays out the scrutiny role of the Parliament by mandating that the President of the Council and the Commission report to it on the results of multilateral surveillance.

Of particular significance is Article 121(5)'s explicit empowerment of the Parliament's "competent committee" to invite the Council President for exchanges of views once recommendations are made public. This explicit reference to “competent committee” de facto entrusts scrutiny powers at the committee level, granting a legal basis for granular oversight by the competent parliamentary committee level for the decisions undertaken in the area of multilateral surveillance. The only other reference to the “competent committee” in the Treaty is to be found in Article 284(3) TFEU on the scrutiny of the euro area monetary policy of the ECB.[6]

Finally, Article 126 of the TFEU provides for a consultative role of the European Parliament with regards to changes to secondary legislation on the excessive deficit procedure and a right of information on decisions taken in this domain.

These provisions in primary legislation ultimately create the conditions for the European Parliament to provide critical legitimacy and accountability for decisions taken at EU level under the economic governance framework.

Secondary legislation - Operationalising Parliamentary Oversight

Secondary legislation further outlines the articulation of scrutiny powers of the European Parliament in the area of economic governance. In particular, by requiring that the European Parliament is fully involved in the European Semester, secondary legislation provides for the procedures to ensure that the European Parliament can exercise its oversight role. This concretely takes form of the possibility to express its views by means of resolutions, organise scrutiny hearings (notably Economic Dialogue) and adopt common positions on the economic priorities of Member States and of the EMU.

Several provisions in the Six-Pack and Two-Pack granted the EP oversight powers notably by establishing Economic Dialogues between the EP and other EU institutions (Commission, Council and Eurogroup).The Economic Dialogue expands the powers of the responsible parliamentary committee to invite such actors to a public hearing to discuss actions and decisions in the remit of the economic governance framework ranging from decisions under the preventive and corrective arms of the SGP to activities related to the MIP to sanctions and fines. The legal framework also provides for cases where a Member State might be invited to an Economic Dialogue (e.g. when subject to an excessive imbalance procedure, sanctions or post-programme surveillance). Nevertheless, the European Parliament retains the right to invite a Member State to a hearing regardless of a specific legal basis.

The recent revision of the preventive arm of the Stability and Growth Pact has also recognised the need to expand the European Parliament’s information rights from the Commission and retained the reporting obligations for both the Council and the Commission on the decisions taken. Please refer to the dedicated section below for more details.

Role in the RRF

The European Parliament has directly contributed to shaping the RRF as co-legislator, thus securing a privileged role in overseeing its implementation. From a parliamentary perspective, the RRF Regulation mirrored existing provisions on the role of the European Parliament in the economic governance framework while providing for a clear right to be informed and heard.

Importantly, the Regulation has replicated the current provisions on the Economic Dialogue by establishing a Recovery and Resilience Dialogue (RRD) with the European Commission that should take place every two months in the competent committee to take stock of major steps in the implementation of the Facility. Relative to the Economic Dialogue formulation of the Two-Pack and the Six-Pack, the article is quite granular in detailing the matters to be discussed. Consequently, the more specific nature of the RRD has served as inspiration for strengthening and clarifying the role of the European Parliament in the new preventive arm of the SGP in 2024 (more details below).

Furthermore, the Regulation mandates that the opinion and views of the Parliament emerging from the RRD as well as relevant parliamentary resolutions are duly accounted for by the European Commission. This formulation strengthens the link between the executive and the legislative branch (i.e. parliament) by setting an expectation that the Commission follows up to parliamentary scrutiny activities.

The RRF was innovative in further raising the profile of the Parliament by requiring that it is kept informed without delays and on an equal footing as the Council. This concretely means that any information transmitted by the Commission to the Council or its preparatory bodies is simultaneously made available to the Parliament, which is also entitled to receive the relevant conclusions of discussions held in such preparatory bodies.

Analysis of the First Decade of Economic Governance (2011-2021)

The first decade of the European Union's reformed economic governance framework, spanning from 2011 to 2021, witnessed significant developments in the European Parliament's role in fiscal and economic policy oversight. This period, marked by the implementation of the Six-Pack and Two-Pack regulations, as well as the introduction of the European Semester, provides a rich context for analysing the evolving nature of parliamentary scrutiny in EU economic governance.

Quantitative analysis of Economic Dialogues

The Economic Dialogue, introduced by the Six-Pack and Two-Pack regulations, has become a cornerstone of the European Parliament's oversight function in economic governance. A comprehensive analysis of these dialogues reveals important patterns in terms of frequency, participation, and content.[7]

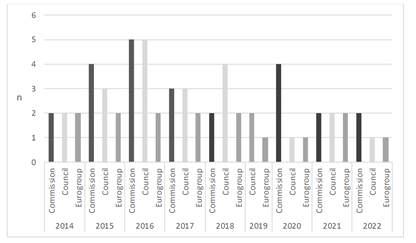

Between 2014 and mid-2022, the Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) Committee of the European Parliament consistently organised at least two meetings per year with the European Commission, specifically with the Commissioner(s) responsible for Economic Affairs. Some of these dialogues were held jointly with the Employment and Social Affairs (EMPL) Committee, broadening the scope of parliamentary scrutiny. The Vice-President for the Euro and Social Dialogue (2014-2019) and the Executive Vice-President for an Economy that Works for People (2019-2024) have been regular attendees, underscoring the high-level engagement in these dialogues.

In addition to the exchanges with the Commission, the ECON Committee held annual meetings with the Eurogroup President, ranging from one to two sessions per year. The Committee also engaged in dialogues with the Council, represented by the Ministers of Finance of the member states holding the six-month Presidency, with the frequency varying from two to five meetings annually, peaking at five in 2016.[8]

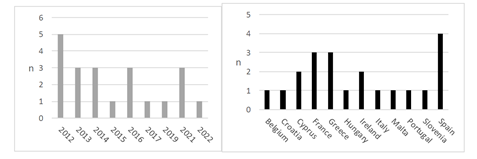

The participation of Member States in Economic Dialogues presents an interesting pattern. These dialogues were more frequent in the immediate aftermath of the economic and financial crisis, with a peak of five meetings in 2012. Notably, Member States that had experienced financial difficulties, such as Spain and Greece, were more frequently involved in these dialogues.

Regarding the content of these dialogues, the questions addressed by MEPs covered a wide range of topics within economic governance, often extending beyond the formal limits set by the legal framework. The focus of discussions varied depending on the institution involved. In dialogues with the Commission, social issues, particularly unemployment and labour market policies, were prominent. The European Semester, especially the implementation of CSRs and the Commission's interpretation of rules, was another significant topic. Dialogues with the ECOFIN Council often cantered on ongoing legislative negotiations between the Parliament and the Council. Exchanges with the Eurogroup president primarily focused on the European Stability Mechanism's financial assistance programs and reforms to the economic governance framework.

The frequency and depth of these dialogues indicate an increased level of parliamentary engagement in economic governance matters. This quantitative analysis could be visually represented by including Graphs 1 and 2 below, which maps the Economic Dialogues with EU institutions and Member States from 2014 to June 2022.

Graph 1: Mapping Economic Dialogue with the other EU institutions (2014 / June 2022)

Source: Bressanelli (2022)

Graph 2: Mapping Economic Dialogue with Member States (2014 / June 2022)

Source: Bressanelli (2022)

Qualitative assessment of EP's impact

The European Parliament's impact on economic governance can be assessed through its influence on policy-making and its effectiveness in holding EU executive actors accountable.

In terms of policy influence, the Parliament has made significant strides. During the negotiation of the Six-Pack and Two-Pack regulations, the EP successfully secured a stronger institutional involvement in economic governance. The introduction of the Economic Dialogue itself is a testament to the Parliament's ability to shape the accountability mechanisms within the governance framework. The EP's role in fostering transparency and accountability was further strengthened in the context of the RRF, where it managed to expand its powers to monitor the implementation of the Facility significantly during legislative negotiations.

A pivotal instance of the European Parliament's impact on economic governance is evident in its intervention regarding Spain and Portugal's fiscal policies in 2016. Following the Council's assessment that these countries had failed to take effective action under the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP), with Spain's 2015 deficit at 5.1% and Portugal's at 4.4% of GDP, significantly overshooting their targets, the EP initiated a "structured dialogue" procedure, as foreseen under Article 23 of the Common Provisions Regulation.

This formalised process allowed for intensive parliamentary scrutiny. The EP organised joint committee hearings with Commission representatives and the finance ministers of Spain and Portugal. During these debates, MEPs advocated strongly against the suspension of EU structural funds, arguing it would be counterproductive and harm vulnerable citizens and regions.

As highlighted in the EP press release, MEPs contended that suspending funding "would only undermine investment, harm their economies and alienate their citizens from the EU project." The Parliament's intervention went beyond voicing concerns; it ensured transparency by staying informed of all decisions related to potential sanctions.

This proactive stance proved influential when the Commission ultimately decided to keep the EDP in abeyance for both countries. By exercising its economic dialogue powers, the Parliament steered a more balanced policy course during a sensitive situation with high stakes for two member states, demonstrating its ability to shape critical economic governance decisions while balancing fiscal discipline with broader socio-economic considerations.[9]

Regarding accountability, the Economic Dialogues have emerged as a crucial platform for Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) to scrutinise the actions of the Commission, Council, and Eurogroup. A comprehensive analysis by Edoardo Bressanelli, mapping meetings from 2014 to mid-2022, provides valuable insights into the dynamics of these dialogues.[10] The study reveals that the scope of questions posed by MEPs is expansive, covering all aspects of economic governance and often extending beyond the formal limits of the legal framework. Notably, the focus of discussions varies depending on the institution involved. In dialogues with the Commission, there is a pronounced emphasis on social issues, the European Semester process - particularly the implementation of CSRs - and the Commission's interpretation of economic rules. Conversations with the Council's ECOFIN configuration tend to centre on legislative negotiations between the two institutions, with limited ex-post scrutiny. Dialogues with the Eurogroup President primarily revolve around financial assistance from the European Stability Mechanism and reforms to the overall economic governance framework.

Bressanelli's analysis indicates that over 50% of the questions posed by MEPs request information or justification of conduct, while less than one-third demand changes in decisions or the imposition of sanctions. This pattern underscores the Parliament's role in fostering transparency and accountability. The responses from EU executive actors have generally been explicit or at least intermediate, with only slightly over 10% categorised as non-replies. This suggests a general willingness of EU institutions to engage with parliamentary queries, offering information and providing justifications for their behaviour. However, Bressanelli notes that this engagement rarely translates into commitments to change decisions or policies in direct response to points raised by MEPs.

While the dialogues facilitate transparency, there is significant room for improvement, particularly in terms of follow-up questions and ensuring that the Parliament's input prompts concrete action. This finding highlights the ongoing challenge of transforming parliamentary oversight into tangible policy influence within the EU's economic governance framework.

Challenges and limitations in EP's oversight role

Despite the progress made, the European Parliament faces several constraints in exercising its oversight function effectively. One significant challenge is the complexity of the economic governance framework itself. The coexistence of supranational and intergovernmental legal frameworks, the empowerment of several different executive actors, and the multi-level nature of economic governance, with interactions between Member State and EU actors at different stages of the policy cycle, make comprehensive parliamentary scrutiny challenging.

In addition, the EP's ability to impose consequences for actions (or inactions) of executive actors remains limited. While the Commission is answerable to the Parliament, the Council and the Eurogroup are not directly responsible to the EP. The only potential sanction available is negative publicity through media coverage, which is dependent on the salience of the issue at hand.

Lastly, the effectiveness of parliamentary scrutiny is also hampered by the limited follow-up to questions asked during Economic Dialogues. Follow-up questions are not frequently asked, potentially limiting the depth and continuity of parliamentary oversight.

Overall, while the first decade of the reformed economic governance framework has seen a significant enhancement of the European Parliament's oversight role, challenges remain. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for further strengthening democratic accountability in EU economic governance.

The European Parliament's Role in the New Economic Governance Framework

Overview of proposed changes: enhanced scrutiny powers to the European Parliament

The 2024 reform of the economic governance framework provided a significant opportunity to strengthen parliamentary oversight and align the European Parliament's scrutiny toolbox with powers established in newer regulations, particularly those introduced through the RRF. While the Commission's initial proposal[11] maintained a relatively conservative approach to parliamentary scrutiny, the final agreement significantly enhanced the Parliament's oversight role through several key innovations.

In its original proposal, the European Commission had maintained the legal framework for the scrutiny rights of the Parliament broadly untouched. However, the removal of a reference to the “competent committee” in the article on the Economic Dialogue (then rebranded as European Semester Dialogue) raised issues of potential inconsistency with the broader economic governance legal framework and would have potential downgraded the scrutiny powers of the European Parliament by removing the possibility to hold a more granular scrutiny of executive decisions through the involvement of the responsible parliamentary committee.

The EP negotiating position[12] immediately recognised these shortcomings, suggesting that an additional dialogue at plenary level would be introduced while leaving the committee-level dialogue unchanged. This dual-level approach aimed to preserve detailed technical scrutiny while elevating the political visibility of economic governance debates. To this extent, the EP position also suggested to retain the possibility to invite Member States to a hearing in the committee. This was notably one of the sticking points in negotiations with the Council[13], which maintained the proposals by the Commission on the parliamentary dimension but suggested to remove the existing Dialogue with a Member State. This would have also amounted to a downgrade of the existing role of the European Parliament. Such a removal would have significantly weakened parliamentary oversight of national implementation.[14]

The new preventive arm regulation ultimately retains existing competence of the European Parliament, namely the Economic Dialogues with other EU institutions and Member States[15]. It significantly strengthens these mechanisms by building on such provisions to further enhance the role of the Dialogues, for instance by specifying the minimum bi-yearly appearance of the Commission in the committee. The preventive arm clearly identifies the competent committee as the place for discussing specific details of the multilateral fiscal surveillance cycle, including changes to the methodology of debt sustainability assessments (DSA) underpinning the new fiscal framework. Furthermore, a new plenary-level Economic Dialogue with the Presidents of the EU institutions and the Eurogroup is established to provide a higher-level platform to scrutinise the application of the framework.

In this context, the new preventive arm also expands the powers of the European Parliament in the direction set by the RRF Regulation by mandating that the EP is kept informed on the same level as the Council and without undue delay[16]. This represents a significant advancement in parliamentary access to information. To this extent, the legal text provides a list of information that the EP is entitled to receive from the Commission. While the list is non-exhaustive and provides only the information that as a minimum should be transmitted with undue delay, it establishes an important baseline for parliamentary oversight[17].

Previous reporting obligations from the President of the Council and the Commission in the area of multilateral surveillance are maintained. However, the legal text clarifies the legal nature of interactions with the President of the Eurogroup that is now subject to an obligation to report on an annual basis to the EP on euro area developments in the area of multilateral surveillance[18]. This responds to criticisms on the lack of transparency and accountability of the Eurogroup to the Parliament, notably in light of its growing role as the de facto coordinating body of economic policies in the euro area[19]. Such criticism is also linked to the decreasing frequency of interactions of the President of the Eurogroup in the course of the 9th legislative term[20].

Finally, the European Fiscal Board is also requested to report annually to the EP, which from now on will also play a consultative role in the appointment of its Members.

New provisions for transparency and accountability

The new framework was designed with the goal of providing a more rules-based, country-specific approach to multilateral fiscal planning and surveillance. This shift to a more nationally-owned framework needed to be accompanied by a strengthening of its dimension of democratic accountability to counterbalance the greater discretion granted to both Member States and the European Commission in the design of fiscal consolidation paths and in the application of the framework.

The multi-layer system of economic governance was therefore reinforced in its parliamentary dimension to guarantee that the principle that scrutiny takes place at the level at which decisions are taken continues applying and boost their legitimacy.

The new preventive arm Regulation therefore ensures that the role of the European Parliament is updated with stronger scrutiny powers to effectively monitor the implementation of the rules. On the other hand, legal obstacles prevent the EU from regulating further on the competences of national parliaments, thus leaving it to each Member State to more precisely define the competences of their respective national parliament. The Regulation seeks to however encourage parliamentary involvement by means of disclosure of their inputs in the medium-term fiscal-structural plans and in the annual progress reports.

These changes seek to prevent that the exercises of fiscal coordination becomes a black box. To this extent, the new information requirements to the European Parliament and the more clearly structured reporting obligations through the Dialogues are a positive step towards better democratic ownership of the decisions undertaken at the European level. By providing a new platform for involvement of the plenary of the Parliament in the scrutiny of the actions of the EU institutions, the reformed preventive arm may raise the profile of the EP as a watchdog of other institutions and further provide political momentum to scrutiny actions in the context of the European Semester. This could more markedly allow to focus on progress on annual EU priorities and potentially better provide a follow-up to the implementation of country-specific recommendations and of the Euro Area Recommendation.

The new framework also further structures the interaction between the EP and the Commission by setting a minimum frequency for appearance in front of the competent committee. While the Commission is reluctant to a binding obligation to accept such invitations, in reality Bressanelli (2022) notes how it “is required to participate in the Dialogues because the ‘Six Pack’ and the ‘Two Pack’ are based on the Treaty provisions that oblige the Commission to reply orally or in writing to the Parliament’s questions” (Articles 14(1) TEU and 230(2) TFEU). Furthermore, by introducing an explicit power for the competent committee of the EP to invite the Commission to explain its DSA methodology, the new preventive arm recognises the European Parliament as de facto the only institution to which the Commission is accountable when determining the fiscal sustainability of the Member States. Consequently, the new requirement for the Commission to defend any changes to its DSA methodology in the European Parliament, as well as the accompanying obligations to ensure replicability, provides strong democratic ownership to a methodology that underpins the entire economic governance framework.

Potential challenges and opportunities for the EP

The scrutiny framework relies on a system of trust and transparency between the institutions. The Commission remains in the driving seat when it comes to timely share information with the European Parliament. Similarly, the quite broad wording of the article on information requirements leaves much discretion to the Commission to decide when and what to transmit to Council and Parliament. On the other hand, its formulation also provides flexibility for co-legislators to request information other than those included in the de Minimis list.

The new transparency provision and the enhanced role of the European Parliament cover only the interactions in the context of the preventive arm of the SGP. However, to establish a meaningful interinstitutional dialogue and effective commitment to transparency, the Commission should adopt a comprehensive approach ensuring that the same level of transparency and communication is applied across the entire economic governance framework, therefore including also legislation that was not subject to review in 2023-2024. Consistency will be key to ensure a uniform application of scrutiny powers in the economic governance framework.

The reformed framework sought to clarify the ambiguous relationship with the Eurogroup, whose President is now obliged to report to the European Parliament on relevant euro area developments. This represents a major opportunity to provide more transparency to an institution that has often been criticised for its opacity. It remains to be seen whether this will concretely translate into a more regular Dialogue with the President of the Eurogroup. The established practice was to hold two Economic Dialogues each year. However, during the 9th parliamentary term only 6 Economic Dialogues took place: two with Mario Centeno and four with Pascal Donohoe since he took the helm of the institution in 2020.

The new plenary level dialogue represents a step in the right direction to strengthen the link with the European Semester. More generally, the new preventive arm has reiterated that the European Parliament remains embedded at the heart of the Semester. However, a concrete obligation for the Commission to respond to the view emerging in plenary and in committee is still missing. The RRF introduced an obligation for the Commission to take into account “any elements arising from the views expressed through the recovery and resilience dialogue, including the resolutions from the European Parliament if provided”. A similar obligation in the context of the economic governance framework would be welcome to ensure a clear follow up to the positions of the European Parliament.

Looking forward, the framework's success in enhancing democratic accountability will depend on how these new provisions are implemented in practice. The Parliament's ability to leverage its strengthened position, particularly through effective use of both committee and plenary dialogues, will be crucial. Moreover, the interaction between enhanced parliamentary oversight and the framework's increased flexibility for national fiscal policies will require careful monitoring to ensure democratic legitimacy is maintained alongside effective economic governance.

Interparliamentary Cooperation on Economic Governance

Legal basis and objectives

Interparliamentary cooperation plays a vital role in EU economic governance by enabling collective parliamentary oversight of increasingly complex and interconnected economic policies. This cooperation is particularly crucial given the spillover effects of national economic decisions within the EU and the need to ensure democratic accountability in areas where executive decision-making has become more intertwined. The emergence of new economic governance mechanisms following the financial crisis, including the European Semester and enhanced budgetary surveillance, has made such cooperation even more essential.

The legal framework for this cooperation rests on multiple pillars. Article 9 of Protocol 1 to the Treaty of Lisbon establishes the general basis for interparliamentary cooperation, stating that the European Parliament and national parliaments shall together determine its organisation and promotion. More specifically, Article 13 of the Fiscal Compact mandates the creation of a conference bringing together representatives of relevant parliamentary committees to discuss budgetary policies and other treaty-related issues. This legal foundation was further strengthened in 2015 with the adoption of formal Rules of Procedure for the conference, which established detailed provisions regarding its organisation, functioning, and decision-making processes.[21] These rules notably specify that the conference shall provide a framework for debate and exchange of information to strengthen cooperation between national parliaments and the European Parliament, while ensuring democratic accountability in economic governance and budgetary policy.

Interparliamentary Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance

The Interparliamentary Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance meets twice yearly, with meetings strategically timed to align with the European Semester cycle. The first semester meeting takes place in Brussels, co-hosted by the European Parliament and the presidency parliament, while the second semester meeting is hosted by the member state holding the Council presidency. This structure ensures regular dialogue while maintaining a connection to both EU-level and national parliamentary processes.

However, the conference's effectiveness in fostering meaningful cooperation has been the subject of debate. Critics have pointed out that it often functions more as a forum for general discussion than as a genuine oversight mechanism. The conference's inability to adopt binding decisions and its largely consultative nature have led some observers to question its capacity to effectively influence EU economic governance. Moreover, the varying size of national delegations and the sometimes limited participation of senior parliamentarians have at times undermined its political weight. Some scholars have also noted that the conference's discussions can remain at a superficial level, failing to achieve detailed scrutiny of specific economic governance measures.

Nevertheless, the conference has demonstrated some value in fostering cooperation and exchange of best practices. It has created a platform for parliamentarians to discuss and compare national approaches to implementing EU economic governance requirements, particularly important given the interdependence of national economies. The conference has enabled parliamentarians to better understand the broader implications of national economic decisions and their potential spillover effects. Furthermore, it has facilitated learning from different national experiences in addressing common challenges, such as implementing country-specific recommendations or managing fiscal consolidation while maintaining growth-enhancing investments. While these achievements may fall short of the conference's ambitious goals, they represent important steps toward enhanced parliamentary cooperation in economic governance.

Challenges and opportunities in fostering cooperation

The coordination between national parliaments and the European Parliament has faced several challenges. A fundamental tension exists between the European Parliament's desire to maintain its position as the primary parliamentary body at EU level and national parliaments' aim to establish a more balanced system of joint scrutiny. Additionally, practical challenges such as different parliamentary calendars, varying committee structures, and linguistic barriers have complicated coordination efforts.

Nevertheless, interparliamentary cooperation presents significant opportunities for enhancing democratic legitimacy in EU economic governance. By bringing together parliamentarians from both levels, it helps bridge the democratic gap in increasingly complex governance mechanisms. The conference provides a platform for combining the European Parliament's expertise in EU-level oversight with national parliaments' detailed understanding of domestic economic conditions and constraints as well as their role in adopting national budgets and reforms. This multilevel parliamentary scrutiny could potentially lead to more effective and democratically legitimate economic governance, provided that cooperation is strengthened. Moving forward, the success of interparliamentary cooperation will depend on finding ways to harness these complementarities while respecting the distinct roles and competencies of parliaments at both levels.

Conclusion

The evolution of the European Parliament's role in economic governance reflects broader transformations in EU democratic accountability. From its initial limited consultative function, the Parliament has emerged as an increasingly significant actor in economic policy oversight, though one whose full potential remains constrained by institutional complexities and competing visions of parliamentary control.[22]

The European Parliament's strengthening has occurred through three key developments: the Treaty of Lisbon's establishment of co-legislative powers in multilateral surveillance; the Six-Pack and Two-Pack regulations' creation of Economic Dialogues; and most recently, the RRF and 2024 governance reform's enhancement of information rights and dialogue mechanisms. These changes highlight the crucial importance of parliamentary oversight in ensuring democratic legitimacy as economic policy coordination has become more complex and intrusive.

However, significant challenges persist. The tension between centralised oversight through the European Parliament and joint scrutiny involving national parliaments remains unresolved. Whilst interparliamentary cooperation has developed through mechanisms like the Article 13 Conference, finding the right balance between European and national parliamentary prerogatives continues to be problematic. Moreover, the practical implementation of oversight tools often falls short of their formal potential, with limited follow-up to parliamentary input and varying levels of engagement from executive actors.

Looking ahead, three developments will be crucial. Firstly, the implementation of the 2024 reforms will test whether strengthened oversight provisions translate into more effective parliamentary scrutiny in practice. Secondly, as the governance system moves towards more country-specific approaches, ensuring effective parliamentary scrutiny whilst respecting national ownership becomes increasingly important. Finally, the broader evolution of economic governance will likely create new challenges for parliamentary oversight, requiring continued adaptation of scrutiny tools and practices.

The experience suggests that whilst formal oversight powers are important, their effectiveness ultimately depends on how they are implemented. Strengthening democratic accountability will require not only robust formal mechanisms but also sustained political will to make these mechanisms work in practice.[23]

(*) Disclaimer: This paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Parliament. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Parliament.

[1] The evolution from the original Stability and Growth Pact of 1997 to the current framework reflects increasing complexity, with the addition of the Six-Pack (2011), Two-Pack (2013), Fiscal Compact (2012) and most recently the RRF (2021) and reformed SGP (2024).

[2] For detailed analysis of accountability challenges in EU economic governance, see BARRETT, Gavin, "European Economic Governance: Deficient in Democratic Legitimacy?", Journal of European Integration, 40(3), 2018, pp.249-264. Available at: Taylor & Francis

[3] The framework combines elements of EU law (Six-Pack, Two-Pack) with intergovernmental treaties (Fiscal Compact, ESM Treaty), creating what some scholars have called a "constitutional hybrid". See Fabbrini F. (2016), "Economic Governance in Europe: Comparative Paradoxes and Constitutional Challenges".

[4] See the principle set out in the “European Council conclusion on completing EMU” adopted on 14 December 2012. Available at: European Council.

[5] Article 121(6) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union: “The European Parliament and the Council, acting by means of regulations in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, may adopt detailed rules for the multilateral surveillance procedure”.

[6] For a discussion on the role of primary and secondary legal provisions on the accountability powers at the level of the competent committees of the European Parliament in the EMU context, please see Hagelstam et al. (2023) “Enhanced political ownership and transparency of the EU economic governance framework”. Available at: European Parliament.

[7] For a comprehensive analysis of this period, see CRUM, Ben, "Parliamentary Accountability in Multilevel Governance: What Role for Parliaments in Post-Crisis EU Economic Governance?", Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 25(2), 2018, pp..268-286. Available at: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

[8] Data from EGOV analysis shows that between 2014-2022, there were on average 2.5 dialogues per year with the Commission, 1.5 with the Eurogroup, and 3.2 with the Council presidency.

[9] This intervention demonstrated the European Parliament's ability to influence decisions through structured dialogue procedures, though some scholars argue it also highlighted limitations since the EP could only advise against sanctions rather than formally prevent them.

[10] BRESSANELLI, Edoardo, Democratic control and legitimacy in the evolving economic governance framework, Study requested by the ECON committee, Economic Governance Support Unit, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 699.553, November 2022. Available at: European Parliament

[11] Please refer to COM (2023) 240 and COM (2023) 241, 26.4.2023.

[12] Report - A9-0439/2023, European Parliament. Available at: European Parliament.

[13] Mandate for negotiations with the European Parliament of 20 December 2023. Available at: Council.

[14] For further discussions on differences between the negotiating mandates of the two co-legislators, please refer to MAGNUS, Marcel, DE LEMOS PEIXOTO, Samuel, LOI, Giacomo, and SABOL, Maja, Economic Dialogue with the European Commission on the EU Fiscal Surveillance, Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 755.713, January 2024. Available at: European Parliament.

[15] Articles 27, 28 and 29 of Regulation (EU) 2024/1263 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2024 on the effective coordination of economic policies and on multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97.

[16] See also Article 25 of Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

[17] Article 27(6) of Regulation (EU) 2024/1263 is non-exclusive in its reference to the information that have to be provided to the Parliament by indicating that “at least the following information” shall be made available, leaving in the scope of the transparency any information that the Commission prepares and transmits to the Council in the context of the application of the Regulation.

[18] For more discussions on the legal relationship between the Eurogroup and the European Parliament before the 2024 reform of the EU economic governance framework, please see also BRESSANELLI, Edoardo, op. cit.; Mark BOVENS and Deirdre CURTIN discuss more broadly the accountability of EU executive powers to the Parliament in “An unholy trinity of EU Presidents? Political accountability of EU executive power”, In CHALMERS, Damian, JACHTENFUCHS, Markus, and JOERGES, Christian (eds), The End of the Eurocrats’ Dream. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.190-217. Available at: Utrecht University

[19] Samuel De Lemos Peixoto and Giacomo Loi argue that the new obligation for the President of the Eurogroup to report to the European Parliament on euro area developments under the preventive arm “allows to acknowledge the unique nature of the Euro group and underscores the need for enhanced transparency”. See: DE LEMOS PEIXOTO, Samuel, and LOI, Giacomo, “The new EU fiscal governance framework”, In-depth analysis, Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 760.231, July 2024. Available at: European Parliament.

[20] K. Hagelstam et al. discuss how Economic Dialogues with the President of the Eurogroup have become less frequent. See: HAGELSAM, Kajus, and LOI, Giacomo, “The role (and accountability) of the President of the Eurogroup”, Briefing, Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 741.497, February 2025. Available at: European Parliament.

[21] The interparliamentary conference's Rules of Procedure were adopted in November 2015 after lengthy negotiations, reflecting tensions between different visions of parliamentary oversight. See COOPER, Ian, "The politicization of interparliamentary relations in the EU: Constructing and contesting the ‘Article 13 Conference’ on economic governance", Comparative European Politics, vol. 14(2), 2016, pp.196-214. Available at: Springer

[22] This evolution mirrors broader trends in EU institutional development, balancing supranational and intergovernmental elements while seeking to address the "democratic deficit".

[23] The experience of the RRF implementation (2021-2024) suggests that enhanced formal powers can translate into effective scrutiny when backed by clear procedures and political commitment to engagement.